Abstract

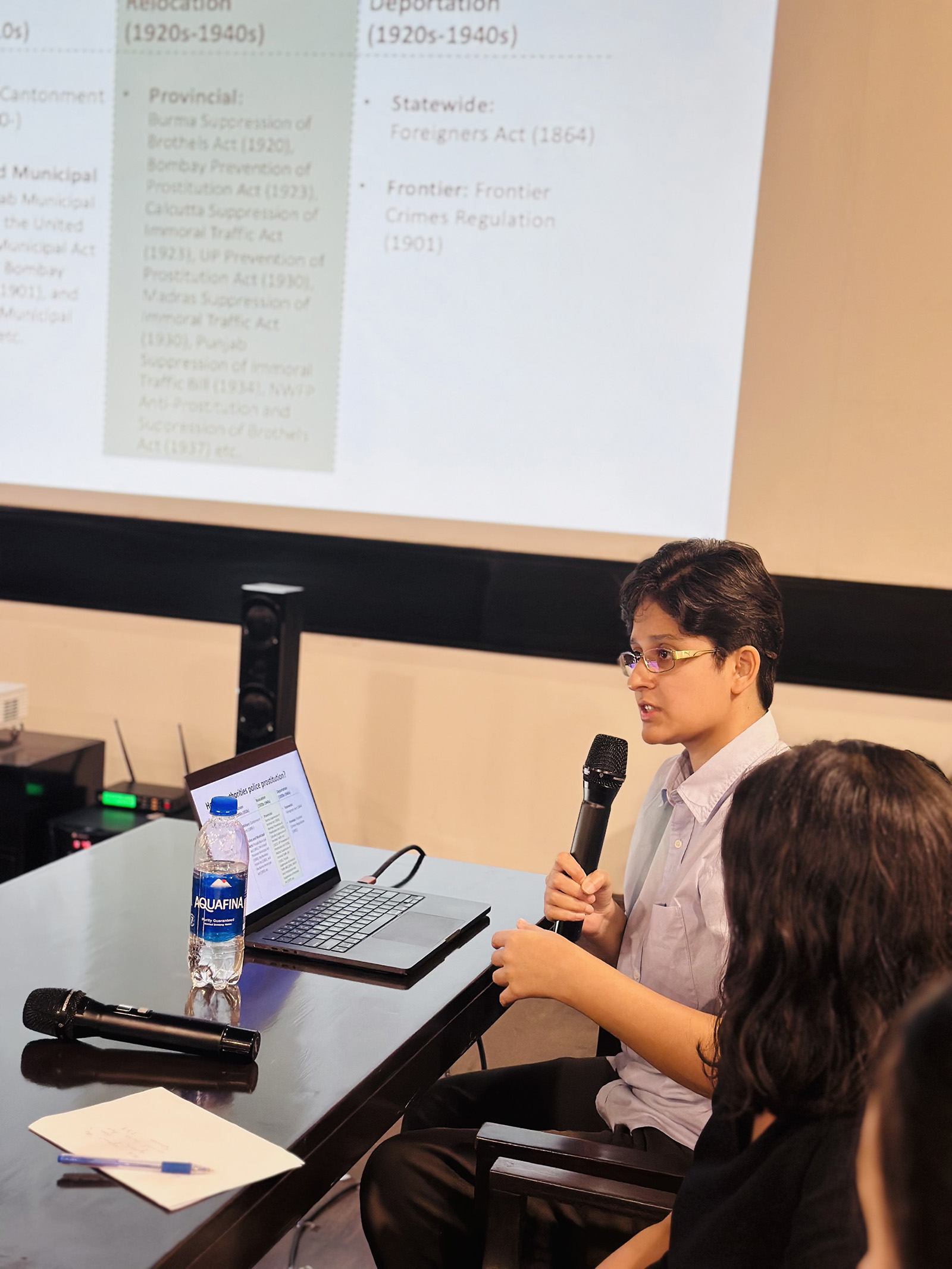

In late-colonial India, the municipal, provincial, and statewide policing of prostitution through spatial control and cordoning revealed the functioning of law as a scattered terrain of disruption rather than a coherent instrument of governance. Colonial authorities attempted to “put prostitution in its place” by policing brothels, cantonments, and border crossings, producing legal categories of deviance and spatial zones of tolerance. Yet these efforts were repeatedly thwarted. Women petitioned against relocations, deportations, and expulsions, and exploited jurisdictional overlaps to elude regulation. These improvisations not only unsettled colonial strategies of control but also showed how prostitution was central to the production of law and the gendered geography of empire. By centering “trouble” as both historical reality and method, the talk reframed prostitution’s place in colonial historiography. Rather than treating it as a problem of vice or as evidence of women’s victimhood, the speaker argued that prostitution was constitutive of the legal and spatial order itself. Prostitution regulation became a site where law’s contradictions were most exposed, as everyday confrontations forced the state to renegotiate its authority. Attending to these histories shows that empire was less a system of seamless control than a fragile project sustained through contestation, and that women’s engagements with the law unsettled the boundaries of colonial governance.