Kis Ki Kahani: Approaching the HUM Drama through the Female Viewer’s Gaze

Mina Shoaib

Mina Shoaib is a graduating senior who majored in History with a minor in Psychology. With a background in South Asian studies and a strong research interest in gender, migration and memory studies, she is interested in exploring the affective and oral histories of the Global South through her work.

“Haan beta, waisay wo jo police walay banta hai na dramay mai, wo mujhe bohat pasand hai. Bara dashing lagta hai wo, uniform saaf suthra, crisp sa, acha imaandaar sa admi dikhaya hai unho nai”

My grandmother’s voice crackles over the landline, her previous inquiries about my health and daily fruit consumption abandoned in favor of discussing the many virtues of one of the leads of the drama we’ve been watching together for the past month. With an openness that might seem surprising in the context of an otherwise very traditional intergenerational dynamic, my grandmother and I are able to share (re: gush) about a character we both find, as she so aptly puts it, “dashing”.

This, I argue, is the power and possibility of the HUM Drama. It is a site of potential, of discourse, sharing and community, built up and sustained through its form, content and construction. The act of viewing a drama, reflecting on it, sharing it-each is a profoundly significant moment and experience in the lives of its viewers, predominantly Pakistani women.

Through my inquiry, I am interested in considering the significance of the HUM drama in the lives of its female viewers, specifically considering its affective value and its role in shaping community and interpersonal, especially intergenerational dialogue. Particularly, I focus on the narratives and viewership experiences of these women, connecting with them directly to ask “What do these dramas mean to you? What roles do they play in your life?”

My hope here is to center the gazes and voices of these viewers, to add to the existing literature (and criticisms) of the HUM Drama from a position that is rooted within the community, and ultimately to “speak with” rather than “speak at”, when it comes to understanding the value, impact and criticisms of the HUM Drama as a form. To achieve this, I focus on primary outreach frameworks, specifically surveys and interviews, that allow direct contact with these female viewers, focusing on their patterns of viewership, affective insights and evaluations of the drama. To supplement this, I refer to several theoretical frameworks, firstly to underscore the significance of television in building sociality and the experience of “family time”, gain quantitative insights about the impact of HUM dramas on Pakistani audiences, and identify the major criticisms and thematic analyses of the HUM Drama. Beyond this, I also touch upon the broader affective significance of different forms of the drama, particularly the telenovela across cultures.

To situate my questions surrounding HUM Drama viewership and intergenerational bonding, it first becomes important to consider how television or “media-related leisure” has become entrenched in modern life1 as a primary form of pleasure and relaxation, but also, historically, as a way to structure the daily routine such that “family time” was often a practice of collective television time. This approach to viewership, Urresti highlights, was particularly common prior to the expansion of digital media and the dispersal of technology, such that now, the practice of watching television, once a family, even communal endeavor, that was to some degree standardized in terms of timings, content and company, can now be approached as a deeply individual, at times isolating practice. Courtois, who looks at the evolution of viewing patterns and modes across generations, notes the transformation in viewing behaviours across four generations, ultimately concluding that increasing isolated viewing correlates negatively with “intergenerational closeness”2 . Ultimately then, there has been a global transformation in the ways that televisions are engaged with .

To situate my questions surrounding HUM Drama viewership and intergenerational bonding, it first becomes important to consider how television or “media-related leisure” has become entrenched in modern life1 as a primary form of pleasure and relaxation, but also, historically, as a way to structure the daily routine such that “family time” was often a practice of collective television time. This approach to viewership, Urresti highlights, was particularly common prior to the expansion of digital media and the dispersal of technology, such that now, the practice of watching television, once a family, even communal endeavor, that was to some degree standardized in terms of timings, content and company, can now be approached as a deeply individual, at times isolating practice. Courtois, who looks at the evolution of viewing patterns and modes across generations, notes the transformation in viewing behaviours across four generations, ultimately concluding that increasing isolated viewing correlates negatively with “intergenerational closeness”2 . Ultimately then, there has been a global transformation in the ways that televisions are engaged with .

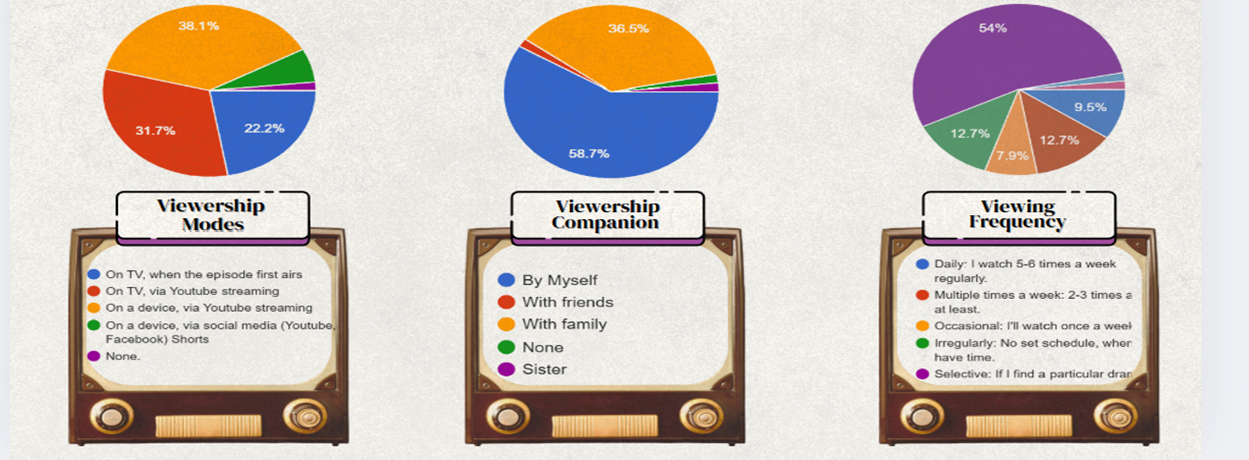

My own inquiry revealed that 49% of the respondents (Pakistani female viewers of HUM Dramas, ranging 25-55 years in age) watch dramas via YouTube streaming, not at the original time of release but according to their schedules/availability. As viewership becomes less standardized, no longer structured along the lines of “family time”, does the HUM Drama serve as a medium of intergenerational communication?

To understand this, I find that the form and content of the drama becomes Dar Si Jati Hai Sila (2017), a drama which deals with intra-family Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) and domestic abuse, elicited a fierce debate among her aunts and mother about the realities of sexual abuse in Pakistan, a conversation that she felt would ordinarily have been hushed away and dismissed. The drama then becomes a kind of propelling force that, through its fictionalization of social realities, allows experiential sharing and a possibility of debate on subjects otherwise deemed taboo or inappropriate, especially among ‘elders’.

Alternatively, the HUM Drama also provides a suspended reality, and through it an outlet for nostalgia and immersion. Across 10+ interviews, participants who varied in age, class, employment status and drama preference all emphasized that the act of sitting down to watch their dramas, generally at the end of the day, was one of the most important, if not the only, consistent acts of relaxation they practiced. One participant explained, “I get to sit down for a little while each day, put life to a side and just decompress”, before emphasizing how she often returns to dramas such as Humasafar (2011) and Zindagi Gulzar Hai (2012) as a source of comfort and site of nostalgic escapism. This quality is not unique to the HUM Drama, or even to Pakistan. Studies conducted across the world have highlighted the affective and cultural significance of the Hispanic soap opera in Mexican telenovela in Nairobi 3(Jiwaji 2010), Ghana (Duncan 1995 4), the USA (Lewkowicz 20115 )and more recently, the Korean K-Drama in India (20226 ).

interviews, participants who varied in age, class, employment status and drama preference all emphasized that the act of sitting down to watch their dramas, generally at the end of the day, was one of the most important, if not the only, consistent acts of relaxation they practiced. One participant explained, “I get to sit down for a little while each day, put life to a side and just decompress”, before emphasizing how she often returns to dramas such as Humasafar (2011) and Zindagi Gulzar Hai (2012) as a source of comfort and site of nostalgic escapism. This quality is not unique to the HUM Drama, or even to Pakistan. Studies conducted across the world have highlighted the affective and cultural significance of the Hispanic soap opera in Mexican telenovela in Nairobi 3(Jiwaji 2010), Ghana (Duncan 1995 4), the USA (Lewkowicz 20115 )and more recently, the Korean K-Drama in India (20226 ).

At the same time, the female viewers of these dramas do not shy away from their flaws, particularly when it comes to the depiction of women in virtually every sphere. Situated within and engaging directly and continuously with HUM Dramas7, these women provide firsthand criticisms when it comes to the depiction of women through the lens of motherhood, labor, class, marriage, sexuality, violence and beyond. Scholars Ayat Zaheer and Zahra Tapal look closely at the exact structure of these dramas and how women across HUM Dramas , from Sara in Humsafar (2011), Rafia in Zindagi Gulzar Hai (2012) and Arooba in Hum Kahan Ke Sachay Thay (2021) are all depicted in various problematic ways. Sara, through her sexuality, her affiliation with “Western” ways of life, is coded as one of the major villains of the narrative; Rafia, whose domestic and affective labor goes unacknowledged in large part; Arooba, who suffers immensely at the hands of her husband only to fall in love with him again by the end of the drama, are among many of the lackluster, and for these female viewers, disappointing depictions of women that HUM has put forth over time 8. The participants in my inquiry offer no balms and have no interest in resigning or accepting these dissatisfying depictions.

There is, in fact, a distinct desire and awareness of the potential of the HUM Drama as a mode of representation and even education. One of my interviewees, a family lawyer, describes the relief and excitement she feels watching Yumna Zaidi in Qarz-e-Jaan (2024), where she sees a woman’s ambition and intensity being centered and regaled rather than being mocked or dismissed for a watery romance. Another participant, who has worked with domestic violence nonprofits for the better part of a decade, says she wishes certain episodes from dramas such as Tan Man Neelo Neel (2024) and Yaqeen Ka Safar (2017) should be considered educational content for their depiction of major socio-political issues. For these women, the HUM Drama’s flawed depiction of gender, class, sexuality and their intersections, are real shortcomings that they feel limit the positive impact of these dramas, and regurgitate tired and entrenched narratives, but for them, this is not the endpoint, rather a crucial opening. Dramas like Parizaad (2021) and Kitni Girhain Baaki Hain (2023) are where they choose to direct their viewership, in the hope that this attention will gradually transform the network’s understanding of the kind of stories they want to see being told.

What then, ultimately, does the HUM Drama mean to its female Pakistani viewer? What role does it play in their lives? There is no one, neat answer. The drama is a place of leisure, of intergenerational dialogue, spousal bonding, nostalgic immersion and for some, recognition. It exceeds expectations; it disappoints immensely; it brings laughter; it offers tears from a safe distance. It can be deeply private, almost intimate, or a shared avenue, providing connection and conversation where it would otherwise be difficult. It is a site of burrowing: on the sofa at the end of another long day, the buzzing of life becomes secondary to the familiar fluorescence, as the screen comes to life and the story begins.

What then, ultimately, does the HUM Drama mean to its female Pakistani viewer? What role does it play in their lives? There is no one, neat answer. The drama is a place of leisure, of intergenerational dialogue, spousal bonding, nostalgic immersion and for some, recognition. It exceeds expectations; it disappoints immensely; it brings laughter; it offers tears from a safe distance. It can be deeply private, almost intimate, or a shared avenue, providing connection and conversation where it would otherwise be difficult. It is a site of burrowing: on the sofa at the end of another long day, the buzzing of life becomes secondary to the familiar fluorescence, as the screen comes to life and the story begins.

It is a site of burrowing: on the sofa at the end of another long day, the buzzing of life becomes secondary to the familiar fluorescence, as the screen comes to life and the story begins.

- Xabier Landabidea, Urresti. "Television as an intergenerational leisure artefact: An interdisciplinary dialogue.” Journal of Audience & Reception Studies (2014): 132-155.

- C. Courtois & S.Nelissen. “Family Television Viewing and Its Alternatives: Associations with Closeness within and between Generations.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 62 (2018), 673–69.

- Aamera Hamzaali Jiwagi. “Negotiating the global: How young women in Nairobi shape their local identities in response to aspects of the Mexican telenovela”, Cuando Seas Mia. Diss. Rhodes University, (2010)

- Cynthia Duncan. “Looking like a Woman: Some Reflections on the Hispanic Soap Opera and the Pleasures of Female Spectatorship.” Chasqui (1995), pp. 82–92

- Eva Helen Lewkowicz. “Beyond the happy ending... re-viewing female citizenship within the Mexican telenovela industry”. Diss. UNSW Sydney, (2011)

- Amritha Soman, and Ruchi Kher Jaggi. "Korean Dramas and Indian Youngsters: Viewership, Aspirations and Consumerism." Korean Wave in South Asia: Transcultural Flow, Fandom and Identity. (2022). 169-184

- Ayat Zaheer. “Women, labor and television: a critical analysis of women portrayed in Pakistani drama serials.” Diss. Memorial University of Newfoundland, (2020).

- Zahra Murtaza Tapal. “Suffering women in Pakistani TV dramas: can the diasporic Pakistani relate?. Diss. (2023).