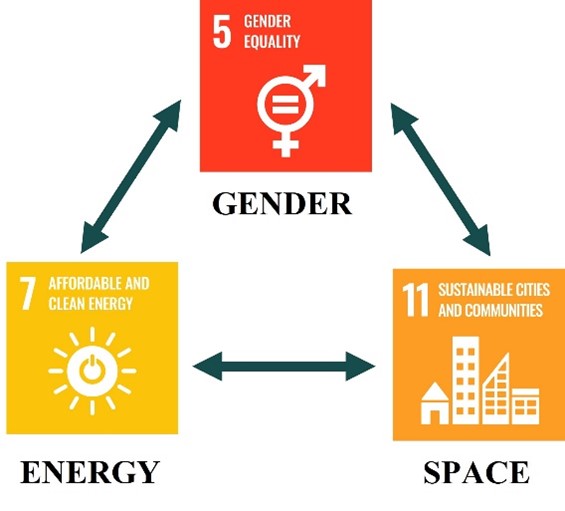

Buildings and spaces are not gender neutral. Their design impacts men and women in different ways - a factor that has been accentuated during the Covid-19 pandemic , and that has implications for the sustainable development of buildings and cities that ensures universal and equitable access. Although gender equality is acknowledged as a key theme across the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), limited focus is given to how gender intersects with other development goals like universal energy access (SDG7) and sustainable growth of cities (SDG11). This three-way intersection and its significance for just and sustainable future transitions needs to be understood by examining each of the links between gender, energy, and space-use, as explained below.

Linking SDG5, SDG7 and SDG11

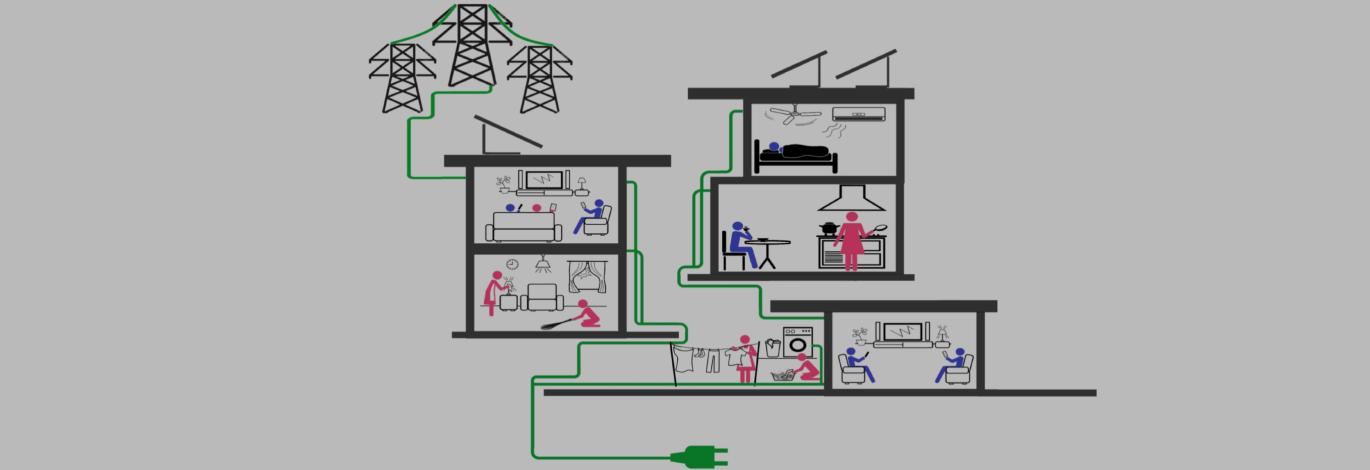

There is a deep connection between energy and space-use. Buildings account for about 40% of global energy consumption and one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and over half of overall electricity demand . This demand is predicted to continue increasing over the coming decades. To meet COP26 targets, estimates show that building energy intensity will have to improve by 30% by 2030 . For investigating energy in the built environment, focusing on building construction and design is important, but equal focus should be given to how buildings are used. This is because ultimately, ‘buildings don’t use energy, people do’ . Studies show that even when buildings are designed to be efficient with low-energy technologies, they can end up using about 3 times more energy than their designed estimates . This is because of variations in occupant lifestyle, behaviour, and socio-cultural practices, which have shown to result in 4-6 times variation in energy demands in similar type of buildings. Hence, it’s important to understand energy as a resource that is used not in and of itself, but for carrying out various activities and practices by its end-users, in line with their social, cultural, and spatial contexts.

The link between energy and space-use is mediated by gender. Specifically, if occupant lifestyles and behaviours play an important role in building energy demand, gender becomes a key factor of difference. Research shows that men and women access, consume, are affected by, and/or benefit from energy practices, policies and services in different ways, due to gendered energy access and gendered technologies . The gendered distribution of energy services can be understood in terms of the division of labour between men and women: Even today in most societies, men are considered as head of the households and breadwinners of the family. On the other hand, women are responsible for at least 2.5 times more unpaid care and domestic work as men , like cooking, cleaning, laundering, household management, and caregiving. Research shows that there is often a clear distinction between women’s work-related use of energy such as in household chores or in home-based income-generating activities (such as tailoring, weaving, etc), while men’s use of domestic electricity is associated with comfort, convenience, and entertainment (such as lighting, air-conditioning, television, etc). Further, women often make more responsible and eco-friendly choices , such as using less air-conditioning and recycling more. A review of Pakistan’s energy policies and interviews with energy experts10 show three key factors that result in women’s differential energy access. This includes a lack of gender-disaggregated data on women’s distinct energy needs; women’s under-representation in the energy and planning sector- in Pakistan, women make up less than 5% of the workforce in power utilities and less than 1/3rd of registered architects and planners ; and gender-neutral energy policies that, because of their gender-blindness, continue to reproduce gender-biased energy outcomes that marginalise women’s energy needs, for example load-shedding schedules that have greater impact on women’s daily routines.

When it comes to planning and development for sustainable cities and space-use, gender again plays a significant role. Notwithstanding that women will form the majority of urban citizens in the coming decades, with ever greater numbers of female-headed-households , women still face numerous barriers and constraints in their access to space within cities. Part of this has to do with the gendered division of labour in the separation of private/public spheres. At the same time, ‘gender-neutral’ planning and policies end up further limiting women’s spatial and energy access.

Urban women experience the built environment differently from men, often with profound disadvantages in terms of less mobility, more vulnerability, and more responsibilities. Subsequent differences in gender roles and relations end up marginalizing women economically, physiologically, socially, sexually. and politically. Whilst we can all agree that this differential access to women’s energy and space exists at the cityscape, which is ‘overwhelmingly designed by men, and for men’ , even the design of domestic spaces can sometimes prove inconducive to women’s privacy and practices, with implications for their energy demand. For example, research on urban middleclass housing in Pakistan shows that contemporary housing follows a Westernised modernist design with ever-greater reliance on mechanical ventilation and cooling. Building regulations often mandate building setbacks, pre-determining the configuration of outdoor spaces, and restrictions on the heights of boundary walls and roof parapets. Unlike the traditional central courtyard havelis of the past, contemporary domestic outdoor spaces provide no privacy or segregation for use by women who are then forced to shift their practices indoors, with greater reliance on indoor comfort. Moreover, even indoor spaces that are often open planned with large glass windows, can hinder women’s privacy and spatial access. This then impacts women’s domestic energy consumption, either directly e.g., through greater use of artificial lighting and cooling when curtains are kept drawn, or indirectly through limiting their space-use outdoors e.g., for household chores and relaxing.

Many such examples show that the house still represents one of the most gendered spaces. Advancements in energy technologies have yet to transform gender roles and relations in most societies. In terms of housing policies, gender-neutrality prevails, meaning we are still far from achieving what Dolores Hayden imagined as ‘the non-sexist city’ . Suffice to say that the links between energy, gender and space use remain significant even today and it is only by critically investigating and targeting intersections between the three, can we truly achieve just and sustainable cities.

Disclaimer: An earlier version of this article was published in The Conversation UK.

Bio: Dr Rihab Khalid is an Isaac Newton Trust Research Fellow at Lucy Cavendish College, University of Cambridge. Her research investigates the socio-technical intersections of gender, energy infrastructure and space use in the Global South. Twitter: @rihab_khalid; LinkedIn: Rihab Khalid, Ph.D