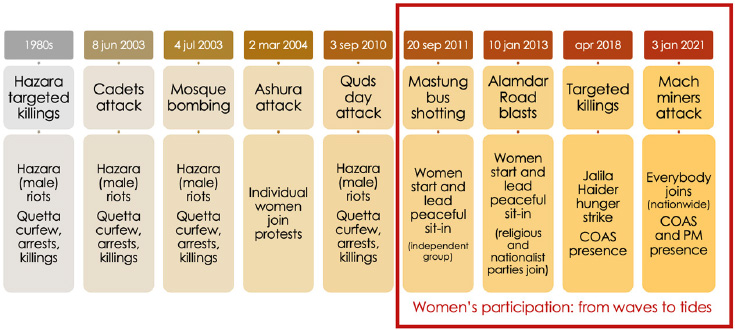

When people think of Hazara protests, they think of Hazara women’s peaceful sit-ins. Yet, the history of Hazara protests in Quetta was traditionally a male-dominated one with a cyclical pattern of violence: a terrorist group attacks, male Hazaras come out to the streets to protest and riot, and the state responds with more violence, curfews, arrests, and killings. It was in this context that the first wave of Hazara women joined public protests following a terrorist attack on an Ashura procession on 2nd March 2004 which killed more than 42 people and injured more than 100. Over time, women started organising themselves and inviting and motivating others to join the protests initially with two main intentions: to show solidarity towards the families of the victims and to protect protesting Hazara men. Their enlarged presence made men more conscious of being less violent during protests, effectively reducing rioting.

TIMELINE OF HAZARA PUBLIC PROTESTS IN QUETTA

In between all these protests more than 3,000 Hazaras were killed in different attacks and seldom did the state bring any of the perpetrators to justice. This has led to changes not only in the nature of the protests, but also in their purpose: from male-dominated violent protests focused on expressions of anger, to female-focused peaceful sit-ins demanding state accountability for a lack of security. As a result, public opinion has softened and several non-Hazara communities have started joining their protests. Yet, despite being key actors in public protests, Hazara women are still excluded from decision-making spaces inside their community and homes.

“There is a discrimination on the basis of gender. Women make the protests successful. But every time when it comes to negotiations, when it comes to decision-making, we rarely see any woman in the meeting.” -Zainab, NGO worker

Why are Hazara women protest leaders unable to transform their temporary public leadership into more enduring forms of influence? We interviewed key female leaders, organisers, and participants in these protests to find out why protest presence and leadership has not resulted in a greater decision-making role. We interviewed activists, politicians, NGO workers, businesswomen, students, schoolteachers, and housewives across a range of ages, levels of education, and social classes. Through our purposive snowball sampling we were also able to ensure that we spoke to women who identify themselves with a range of ideologies.

What did we find? We found the intersection of patriarchy, identity politics, and social structures playing a key negative role on their influence in decision-making processes. The stereotyping they go through and the backlash they suffer all contribute to their inability to transform their temporary public leadership into more enduring forms of influence. The backlash Hazara women get for being outside, claiming action in public spaces – male spaces – is related to the various ways patriarchy works to marginalise women. This is visible in the house, in Hazara social structure, and in politics, with nationalist and religious parties having a particular image of women disconnected from reality. In our conversations with Hazara women protesters we could see three key barriers blocking their visibility as leaders.

First, there is a strong stereotyping of Hazara women based on virtue, obedience, and domesticity where women are invisible as women unless they portray a normative femininity 2 accepted in Hazara culture. The stereotyping is not only manmade: both men and women stereotype women’s participation in protests, including even some women organisers. Reminiscent of Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale – where women are subjugated within a hegemonic patriarchal society and named/identified according to their relationship to men – Hazara women are identified according to their relationship to the (male) victims: as mothers of, wives of, sisters of, or daughters of men. Not as protest leaders.

“In Hazara folklore and history, during 18th century when the soldiers of the Afghan king Abdul Rahman attacked the Hazara, 40 Hazara girls jumped from a mountain and committed suicide. I always ask why women should die? Why can’t they fight and live? This is how they still want women leaders to be: they should die to protect their bodies. Men associate their honour with their women’s bodies”

- Jalila, lawyer and activist

intersection of gender with class, hierarchical social structures, and deep-seated religiosity. Women protest leaders are not only blocked from a decisionmaking role because they are women, but because they are women and of a lower class, or women and of a lower-ranked tribe/sub-tribe, or women and not pious enough. Many of our respondents highlighted the discrimination they face not only connected with patriarchy but to their families’ social status within Hazara tribal society. Politics further intersects with religion, more precisely with religious parties claiming to represent the Hazara plight. Several women activists complained that religious parties force them to dress and behave in accordance with their interpretation of Islam and an ideal Muslim woman. Those not following their defined standards of piety are discriminated against.

A third barrier is that the opposition to women organising and leading protests happens also inside the house, often carried out by close relatives. Hazara women – like Palestinian women3 – end up fighting two fronts: they fight the state, demanding security and accountability; and fight patriarchy from within their community. Throughout South Asian classic patriarchy, women’s identity and bodies are linked to the honour and shame of the family as well as of the community.

“I asked many [men] why your honour is attached to us? Your honour is so fragile if you attach it with my clothes, The backlash Hazara women get for being outside, claiming action in public spaces – male spaces – is related to the various ways patriarchy works to marginalise women. ACADEMIC WORK Image: Hazem Asif | Instagram: @worldofhazem 10 GENDER BI-ANNUAL 2022 my chador and my dupatta, I request you to keep it away from me.”

- Saira, local politician

Under the strong patriarchal hold, women are not only controlled through religious and nationalistic ideologies in public, but also through everyday practices inside the house. Several of our respondents said the harassment and backslash they faced affected their family to a point where family members asked them to stop their activities.

Women who break such barriers and societal stereotypes face both online and offline harassment within the community. Women are shamed and harassed for participating in protests, not only by strangers within the community but by their own family members and close neighbours.

“When my own son was not the victim [of an attack] and I was attending the protests my relatives and neighbours were saying that I am a beysar woman and they were thinking I go there for entertainment.”

-Zahra Khanum, school cleaner

Of the different tactics of shaming and harassing women protest participants both during and after the protests the most common is character assassination on social media. The use of social media is everpresent among the Hazara community. During protests, Hazara men take pictures of women protesters to later name and shame them.

“Women were always made to sit behind the men. If someone tries to come in front, the men used to make their videos and pictures and shaming them publicly: ‘see the behaya woman sitting among men! Her dress is not good! Her hijab is not right!’”

-Sareer, government schoolteacher

Despite always standing for the male members of their community, women protesters face a lot of backlash rooted in tribal and patriarchal norms. As a result, many women feel discouraged to join further protests. Even though they actively take on the state with some success, Hazara women protesters cannot be collectively empowered in the absence of wider shifts in patriarchal social norms.

“Women who have historically been suppressed, who have historically been put to go through so many layers of suppression and so many layers of discrimination that, you know, we actually don’t idealise ourselves. Even in our imagination we don’t put ourselves in those kinds of frames.”

-Saba, journalist

Still, there are visible changes in women’s perceptions of their own role – from young feminists to more conservative ones – such as Fatima’s, a housewife member of the main Shia religious party when she says, “You know they [men] need us now; without us they can’t make their voice heard.”

Jalila Haider is a human rights lawyer and political activist from Quetta. She was named in BBC’s 100 Women of 2019 and was a recipient of the United States Department of State’s International Women of Courage Award in 2020.

Miguel Loureiro is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex. He works at the state-citizen interface from both a citizens’ perspective, examining accountability and empowerment relations, and the state’s perspective, identifying opportunities for state responsiveness.