You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.

- from a compilation of anonymous Afghan folk poetry or landay collected by Eliza Griswold

According to the United Nations, Pakistan has the 6th highest number of girls married before the age of 18 in the world. Child marriage remains prevalent due to deeply entrenched cultural traditions, poverty, lack of awareness and access to education, and lack of or perceived lack of security for women and girls. It has also sustained, despite legal efforts in recent years, by gender norms that prioritize the role of girls as wives and mothers.

The situation is even more dire in countries ravaged by war and violent conflict, like in neighbouring Afghanistan. Here, shattered by extreme poverty and terrified for their daughters’ personal and bodily safety amid conflict, displacement and migration, the drivers of child marriage in communities have only been strengthened and continue to negatively impact girls’ wellbeing.

For many refugee families, displacement-specific challenges have exacerbated girls’ vulnerability to child marriage. For others, especially when mothers are determined to break the cycle and find better opportunities for their children, some resistance to prevalent protection-heavy social norms is seen, leading to marriage postponement and higher levels of education among girls.

“When I was younger, I used to feel angry but I know my parents had no choice. They owed my You sold me to an old man, father. May God destroy your home, I was your daughter. - from a compilation of anonymous Afghan folk poetry or landay collected by Eliza Griswold PRACTITIONER VOICES 5 GENDER BI-ANNUAL 2022 husband a lot of money and he demanded they cough up the cash or hand me over in marriage. I was 12, he was 69. He had a 25-year old son from a previous marriage - I became a mother to a man older than myself.” – S, now 32 years old and a widow.

Exchange marriages, or watta satta as they are called in Pakistan, are alarmingly common in Afghanistan too. Young girls are married off to settle blood money, tribal disputes and property feuds.

“Do you know what a churail looks like?”

I laughed, because we’d been teasing each other about our love of long naps and pulao and wondering if that might have something to do with our weight gain. Like many longsuffering people, Afghan women have learned to use laughter as a survival skill.

“No! I didn’t think they were real. Have you seen one?” “I live with one! Come over one day and I will show you.”

Her tone changes: “It’s my husband - there can be no bigger churail than him.”

R was married at 15 to a man who was 25 years old. She is determined that her daughters will not meet the same fate. This is often a source of conflict with her husband.

Most middle-aged refugee women I met were married between the ages of 12 and 15. They are not educated or their education was halted as soon as they got married. Multiple marriages are common.

The women speak of broken families when they are sent to Pakistan after marriage (“I have not seen my mother and brother in 20 years. I don’t even know if they are alive”). There is a clear sense of yearning for childhood. For loved ones lost. For the beauty of the mountains and the streams they knew. But they can’t go back to the childhood they lost and the sense of country they yearn for. Conflict, poor living conditions, lack of opportunity and the desire to educate their children all keep them in Pakistan.

Exchange marriages, or watta satta as they are called in Pakistan, are alarmingly common in Afghanistan too.

Yet, things are slowly beginning to change among the refugee groups. Many more girls are now being educated and marriage is being delayed. Poverty, displacement and unfulfilled dreams remain common themes in conversations but there is some hope too. Most women cite not being educated as their biggest regret and it is the younger girls’ biggest aspiration. They want to be doctors and architects and change the world they live in.

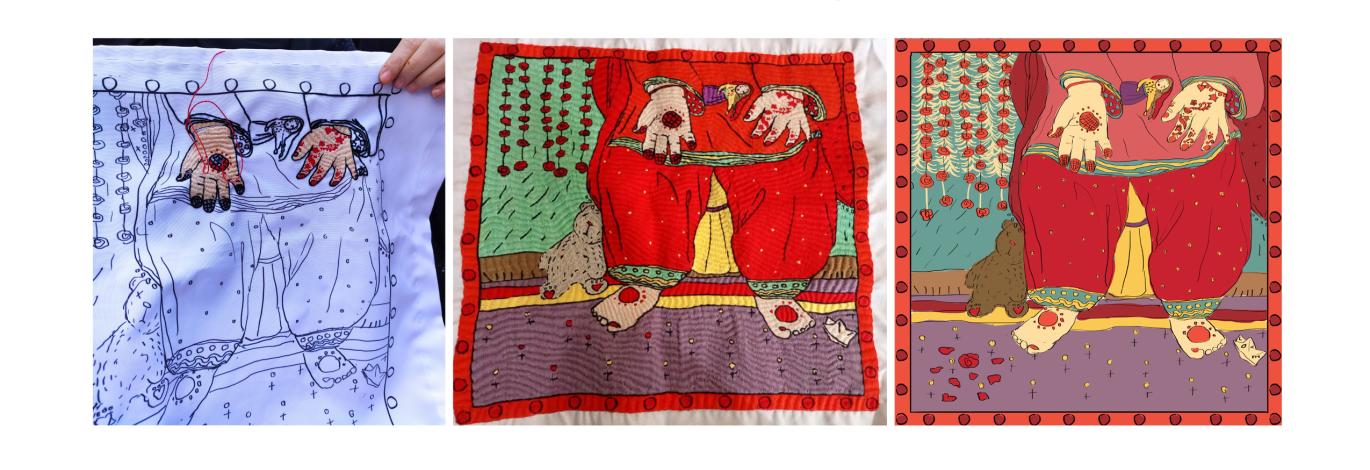

The artwork above was based on one of a series of stories addressing agency, identity and representation from the perspective of Afghan refugee women and girls. It was developed as part of a pilot economic empowerment project delivered in partnership with the UNHCR in Karachi, Pakistan. The artworks were based on the author’s (and project lead) interaction and interviews with refugee women and girls and illustrated using images and stories collected from the field by the author. These were finalised with community input and then handworked by the women artisans themselves. The pieces unmask the lived experiences of a generation continuing to deal with the legacy of conflict and deprivation, where the capacity of traditional handworks to connect people with place, time, history and a sense of being is confirmed. The author acknowledges the inherent tension in the ownership of the piece – does it belong to the artisans that stitched it, the teams that supported the development of investigative narratives and livelihood opportunities via a social development initiative, the donor agency that financed the project or the illustrator who eventually captured the content as an image? But perhaps these conversations are too rooted in an immediate and narrow capitalist understanding of ownership of communal creative output. Perhaps the focus should be the role such works can play in building more empowered narratives such as a shared awareness and understanding that no child should be a bride, no child should become a mother and all girls deserve a chance to a full and happy life.

Amneh Shaikh-Farooqui is an activist and social entrepreneur whose work lies at the intersection of social justice, gender equality, sustainability, and fashion.