Access to justice comprises elements necessary to enable citizens to seek redress for their grievances, including a legal framework that grants human rights, widespread legal awareness and literacy. Availability of affordable legal assistance must be assured.Dispute resolution must be timely, efficient, and impartial. It is only through these elements that access to justice for women can truly be realized.

In Punjab, women face unique challenges due to cultural and social subordination. Limited access to education, awareness, opportunities for economic empowerment, and mobility contribute to an inadequate access to justice. In criminal justice matters, women’s first point of entry into the system is the police, although experts contend that it should instead be a healthcare facility, to allow for timely medical examinations. A lack of confidence in redress mechanisms set up by the government also limits reporting of cases and “efficient dispute resolution”. Data sourced from the Punjab Bar Council evidences that only 1 woman and 3 men were provided legal aid in 2020, depicting an abysmal state of institutional legal aid provision, a key element of access to justice.

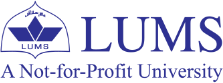

Apathetic attitudes and corruption within the Police, coupled with lengthy trials often discourage women from pursuing cases. Evidence obtained from the Prosecution Department shows that convictions in cases of violence against women have overall remained low at 5 – 6% since 2016, while acquittals have been recorded at 95%. Low convictions present a serious problem for women’s access to justice; one that demands adept solutions.

Furthermore, delays in adjudication, often caused by frequent adjournments, vacant seats in the judiciary and poor case management add to women’s plight. Survivors of gender based violence (GBV) are vulnerable to prejudicial and insensitive comments of Investigating Officers, medical staff at District Headquarter Hospitals (DHQs), lawyers, prosecutors and Judges, thus exposing survivors to a fresh cycle of violence and contradicting the essence of “justice”. Although 4 women police stations exist in Punjab, these lack jurisdiction to function separate from main police stations. Medicolegal examinations are also rarely conducted for victims of sexual violence. Research also shows unavailability of rape kits at some DHQs. Out of Court settlements and financial compromises, frequently entered into even for noncompoundable sexual offences, also limit justice for women. Although all 36 districts in Punjab have at least 1 shelter home for women, travel distance and limited mobility results in women starved for residential options if they choose to leave abusive homes. Furthermore, there exists no long-term rehabilitation or reintegration plan by the Government for women victims of violence.

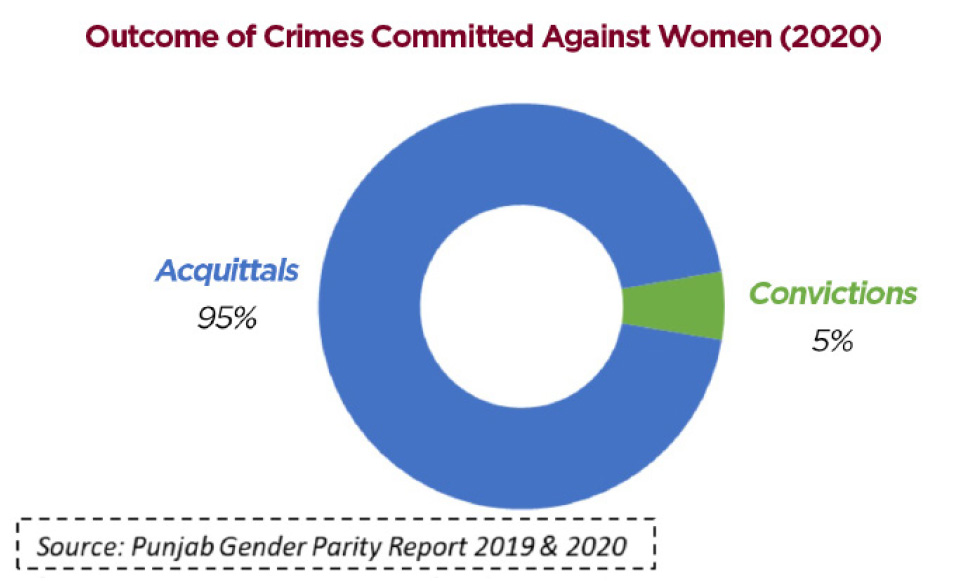

Setbacks in women’s access to justice are also evident through primary data obtained by the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women. The Government-managed SBB Human Rights Centers provided redress to only 1,747 women in 2020, attributable to partial closure of the SBBHRCs and limited redress facilities (such as shelter, legal aid, counseling and rehabilitation services) during the pandemic. Some positive developments, however, have shaped the way for better access to justice for women in the last few years. During 2020, the GBV Court in Lahore continued prosecuting cases of sexual violence. Punjab Police Helpline (15) was used extensively to report crimes committed against women; an increase of 107% was noted in the magnitude of calls received from 2019 to 2020. Punjab Women’s Helpline (1043) provided legal guidance and advice to women regarding criminal, family law, human rights, employment, and inheritance matters. Following the same trend, data sourced from Punjab Women Protection Authority shows uninterrupted operation of the Violence against Women Center in Multan in 2020. Furthermore, presence of women’s help desks and dedicated female staff for GBV cases in 230 police stations in the province by 2020 is a noteworthy milestone. Similarly, the number of police stations in Punjab have also been on the rise since 2018; data shows a total of 720 police stations across the province by 2020, compared with 715 in 2017, thus depicting an improvement in reporting mechanisms.

Apathetic attitudes and corruption within the Police, coupled with lengthy trials often discourage women from pursuing cases.

Another positive development for women’s access to justice is the passage of the 2021 Antirape (Investigation and Trial) Act, which inter alia disallows the “two-finger test” in 2021. Furthermore, addition of more women in Punjab Police; more female prosecutors in the Punjab Public Prosecution Service; periodic gender sensitive training curricula for Judges and Prosecutors; construction of new Violence against Women Centers in Punjab; plans to inaugurate GBV Courts at district level; and active helplines for women’s legal aid and information are welcome developments in Punjab. Loopholes in implementation of these valuable measures must, however be addressed immediately so as to ensure that women’s access to justice improves across the province. To further strengthen access to justice, strategic plans and programs for judicial reform must be developed and service delivery improved. Apart from strengthening the judicial system, these measures are also crucial for achievement of SDG 16.

Aliya Khan has over 10 years of experience working in the development sector on genderrelated projects. She has been working with the Punjab Commission on the Status of Women and UNFPA since 2016.