Evidence from Two South Asian and Two Sub-Saharan African Economies

For a long time, females in many countries have suffered substantial disadvantages relative to males in education and work opportunities. The last thirty years have seen large investments to try to achieve universal primary education by 2015, associated with the Education for All Initiative and the Millennium Development Goals. While this goal was not realised, important progress was made, and school attendance by young people increased substantially. To what extent did this reduce gender gaps in educational attainment? And has it led to equal post education opportunities for both young women and young men?

This comment draws on a research project which analysed labour supply of young females in four countries, two in South Asia (Bangladesh and Pakistan) and two in sub-Saharan Africa (Ethiopia and Rwanda), working collaboratively with researchers from these countries (LUMS was the Pakistan research partner). Education is a critical factor shaping a young person’s labour supply and available work opportunities. But another very important factor also shaping work and education opportunities for young people is the issue of family formation (marriage and childbirth). These are choices young people often face simultaneously and each choice can affect the others.

The increase in completion rates was greater for females than males in the Asian countries, reducing their gender gap, but this was not the case in the African countries.

We consider here the evolution of the gender gap in education attainment and how this relates to work and family formation outcomes. For this purpose, we use comparable data for the four countries collected by Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), not because it is the best source of labour data (it is not), but because it has data on each of these three aspects, is the same for all countries, can be compared over time, and it allows a specific focus on young people. We assess how these outcomes have evolved for young women and men between an earlier and later survey in each country, separated by between 16 and 27 years depending on the country. We focus on young people in the 20 to 29 year age range, by which time they should have completed school education.

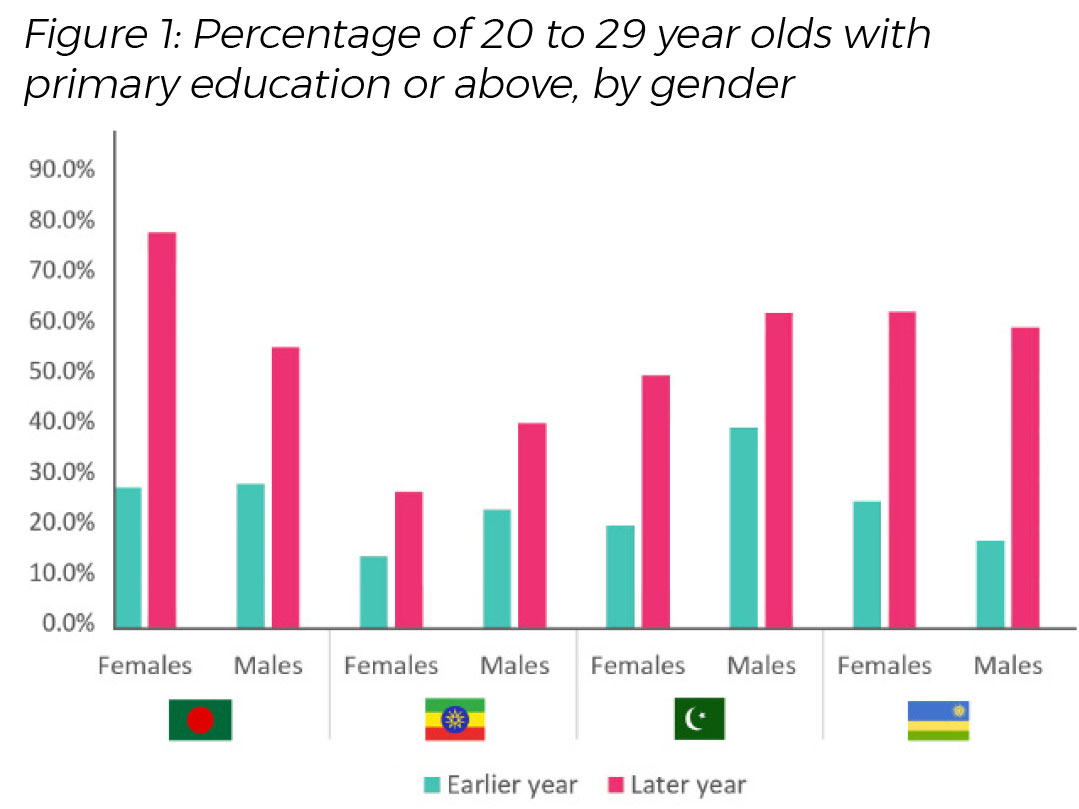

Figure 1 reports gender disaggregated primary completion rates for these four countries in the earlier and later years. In all countries except Rwanda, more males than females had completed primary education in the year of the first survey (between 1990 and 2000 depending on the country). The gender gaps were larger in Ethiopia and Pakistan. The Figure shows that primary school completion rates for this age group have increased substantially in each country. The percentage of young females who now have finished at least their primary education more than doubled in three of the countries, and almost doubled in the fourth, Ethiopia. The increase in completion rates was greater for females than males in the Asian countries, reducing their gender gap, but this was not the case in the African countries. In the later year in Bangladesh more females than males had completed primary school. It is also striking from these figures that primary school completion is still very far from universal in all of these countries.

Fewer from this age group though have achieved education at secondary level or above, reflecting the policy emphasis on primary education; but there have also been substantial increases over this period (from a low base) and a narrowing of the gender gap. Again, the most successful country has been Bangladesh, where now many more females than males are educated at this level. There is also no gender differential in secondary education in Rwanda. But in Ethiopia and Pakistan, as at primary level, a significant gap remains in favour of males. In summary the gender gap is in favour of females in two of these countries but remains sizeable in favour of males in the other two.

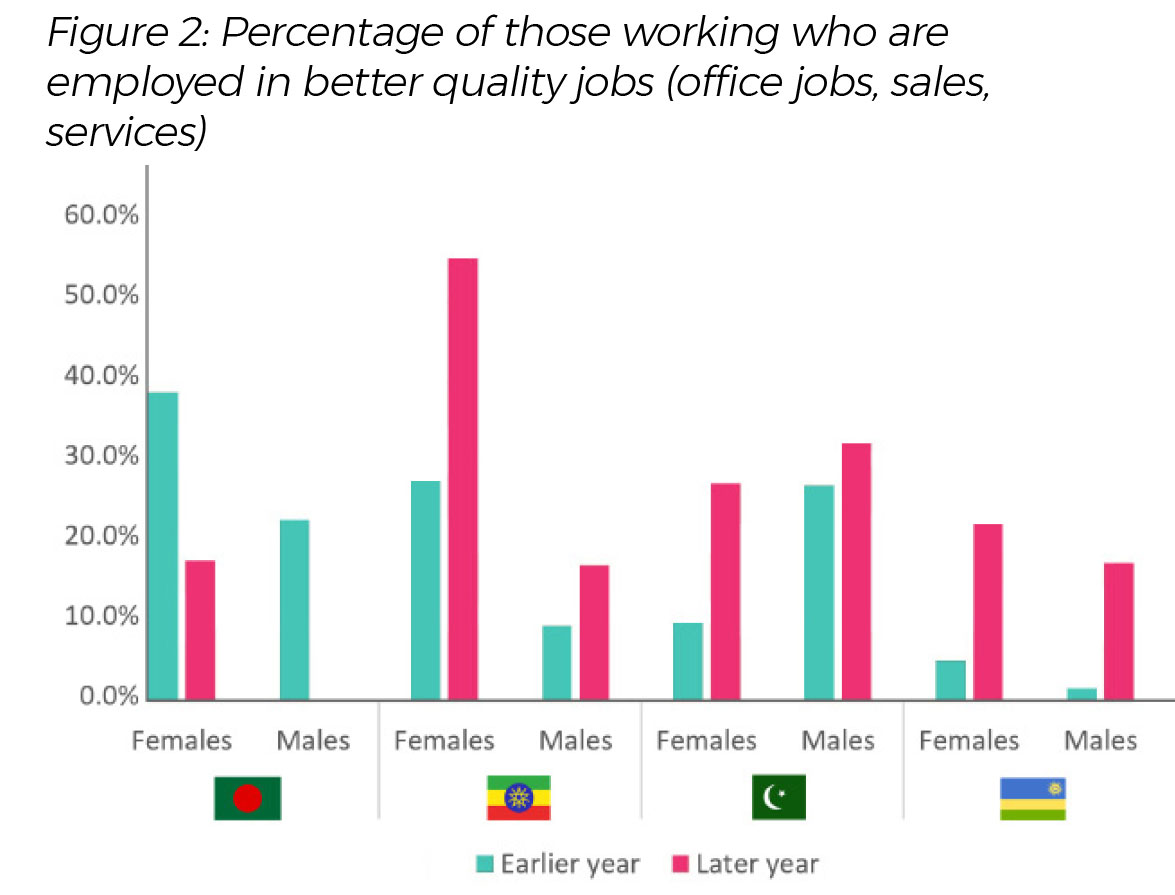

Figure 2: Percentage of those working who are employed in better quality jobs (office jobs, sales, services)

Equally important though is what education enables young people to do afterwards, among which work is a very important consideration. In each of these countries almost all men worked in both the earlier and later surveys. The extent to which females in this age range worked varies by country but is always much lower than for males. The proportion of women able to work fell in all countries except Bangladesh, irrespective of their higher education levels. There is evidence though in these same countries that more of those women who work undertake activities such as office jobs or jobs in sales and services (Figure 2), which may be considered better quality work and is probably enabled by their higher education attainments. However, it is very important to recognise that many with completed primary or some secondary education could not access these better quality jobs, the number of which expanded much more slowly than education levels. In Bangladesh the number of women working increased but the share of them doing better quality jobs fell.

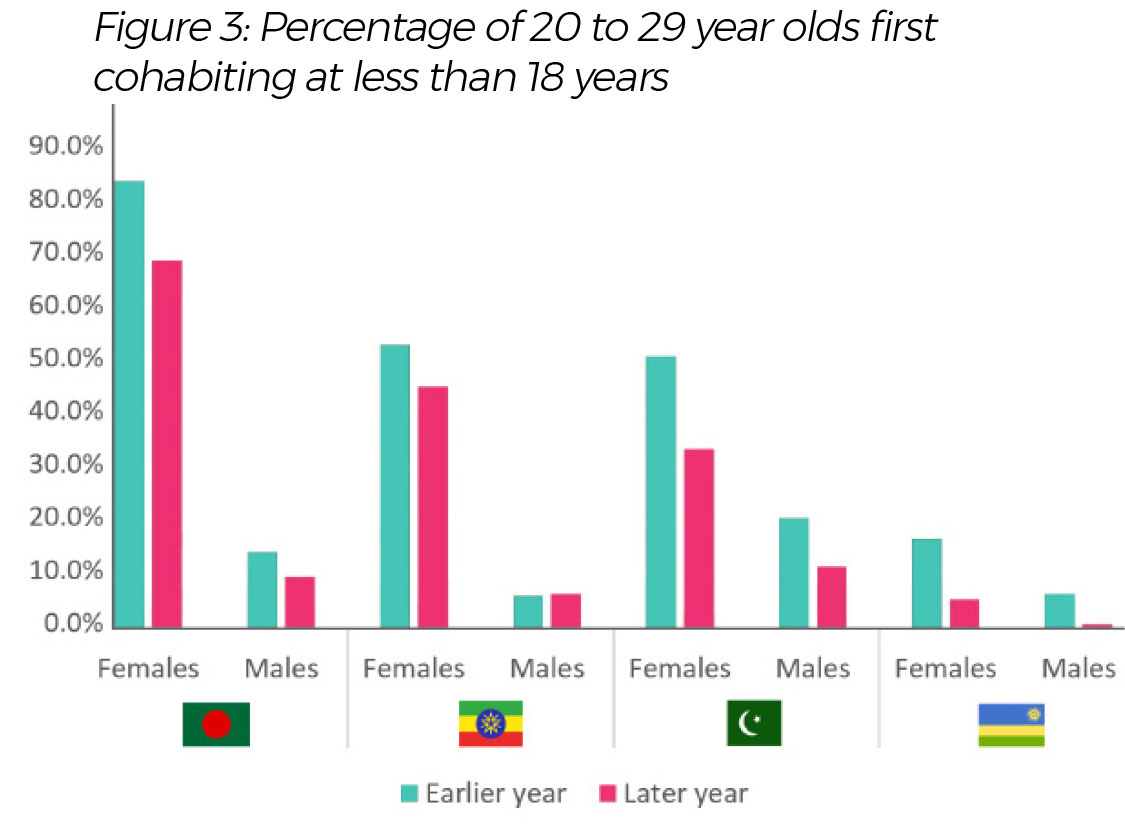

Figure 3: Percentage of 20 to 29 year olds first cohabiting at less than 18 years

In relation to family formation, the data presented in Figure 3 shows very clearly large number of young women in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Pakistan entering into marriage or partnership before the age of 18 years, sometimes under parental influence. Though this has decreased over time, it remains substantial. Significant numbers also became mothers before they reached 18 years. Early marriage or childbirth is accompanied by the end of education in almost all cases, though the causality here is unclear. Some may leave school for many reasons including poverty, poor quality of schools, inadequate provision for girls, or a perception of limited work prospects. Others may marry or become pregnant at young ages and leave school as a result. Figure 3 shows there is a very strong gender dimensions to this: many fewer men entered into partnerships or became parents before 18 years, meaning that many young women are forming partnerships and having children with older men. This earlier entry into family formation for young women substantially limits both their education and work opportunities; these constraints do not exist in the same way for males.

In summary the data shows that for these four diverse countries the past 20 to 25 years have been marked by important increases in levels of educational attainment and a consistent reduction of the gender gap. This has been an important achievement. But at least two countries considered here (and many others) are far from achieving gender parity. Some of those who have achieved higher levels of education, female and male, have often been able to access better quality work in three of the countries, but equally many of those who are now more educated have not been able to access such jobs. There are many more educated young people than there are good jobs. A very large part of the gender gap in work outcomes and also in education though reflects the much greater tendency for young women to form partnerships and have children at younger ages. Even if this has been decreasing over time, it remains very prevalent in three of the countries.

Reducing the gender gap in education, which has happened in all four countries, is only a small part of reducing wider gender gaps which continue to persist.

Appendix:

The data are derived from DHS surveys for the four countries and related to nationally representative samples of young women and men aged 20 to 29 years old at the time of the survey. The survey years are as follows:

- Bangladesh: 1993-4 and 2017-19

- Ethiopia: 2000 and 2016

- Pakistan: 1990-91 and 2017-18

- Rwanda: 1992 and 2019-20

Andy McKay is Professor of Development Economics at the University of Sussex, UK. He researches on various development topics including questions of poverty and inequality, labour and gender.