The built environment is predominantly a by-product of the male vision, or at least that’s what we have been taught and educated to believe. We have inherited design ideologies that influence our homes and our lives which apparently come from a very singular perspective. However, I have often wondered: What agency have other genders had in contributing to our built environment?

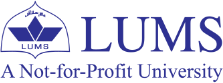

Historically, other genders have, in fact, contributed to very significant structures but their presence and influence remains secondary only to the names of men who were considered a more important association at the time. Seen in the grandeur of the Mughal architecture that spans the subcontinent, there is almost never mention of the influence of women in the design process, yet one of the most notable structures was the undertaking of a bold Mughal queen. The magnificent sandstone structure laced with marble inlays, Humayun’s Tomb, located in Delhi was commissioned by his wife, Bega Begum.[1] This mausoleum served as the template for the Taj Mahal and was largely influenced by Persian design, which Bega Begum sought out by hiring Persian designers. It was significant as it was also India’s first garden tomb with the ‘Char Bhag’ [2] a design so influential that it was adopted in multiple tombs after.

The problem of gender in architecture remains two-fold, one: there has been a great deal of under representation of the other genders in architecture. Even when there have been contributions by other genders, they have lacked acknowledgement, or in the case of Bega Begum, been clumped in with the achievements of a male. Secondly, there have been very limited other gender viewpoints adopted in the built world due to the power structures in place always prioritizing the male perspective. The question remains, where do we go from here?

In the last century, with the advent of one of the most defining movements in architecture, many women have played a valuable role in shaping it. With the celebrated, documented and studied great modern male architects, are the not as well-known female counterparts. Women who produced large, important bodies of work yet were in the shadows of the male architects of the time, such as Lilly Reich to Mies or Charlotte Perriand to Corbusier, to name a few.

Without these women’s contributions - their study of and sensitivity to design and presence - the works of these known masters of the modern architecture movement would be incomplete. Yet even now in academia and beyond we only scratch the surface and wonder where the women are. They are here and they are doing the work.

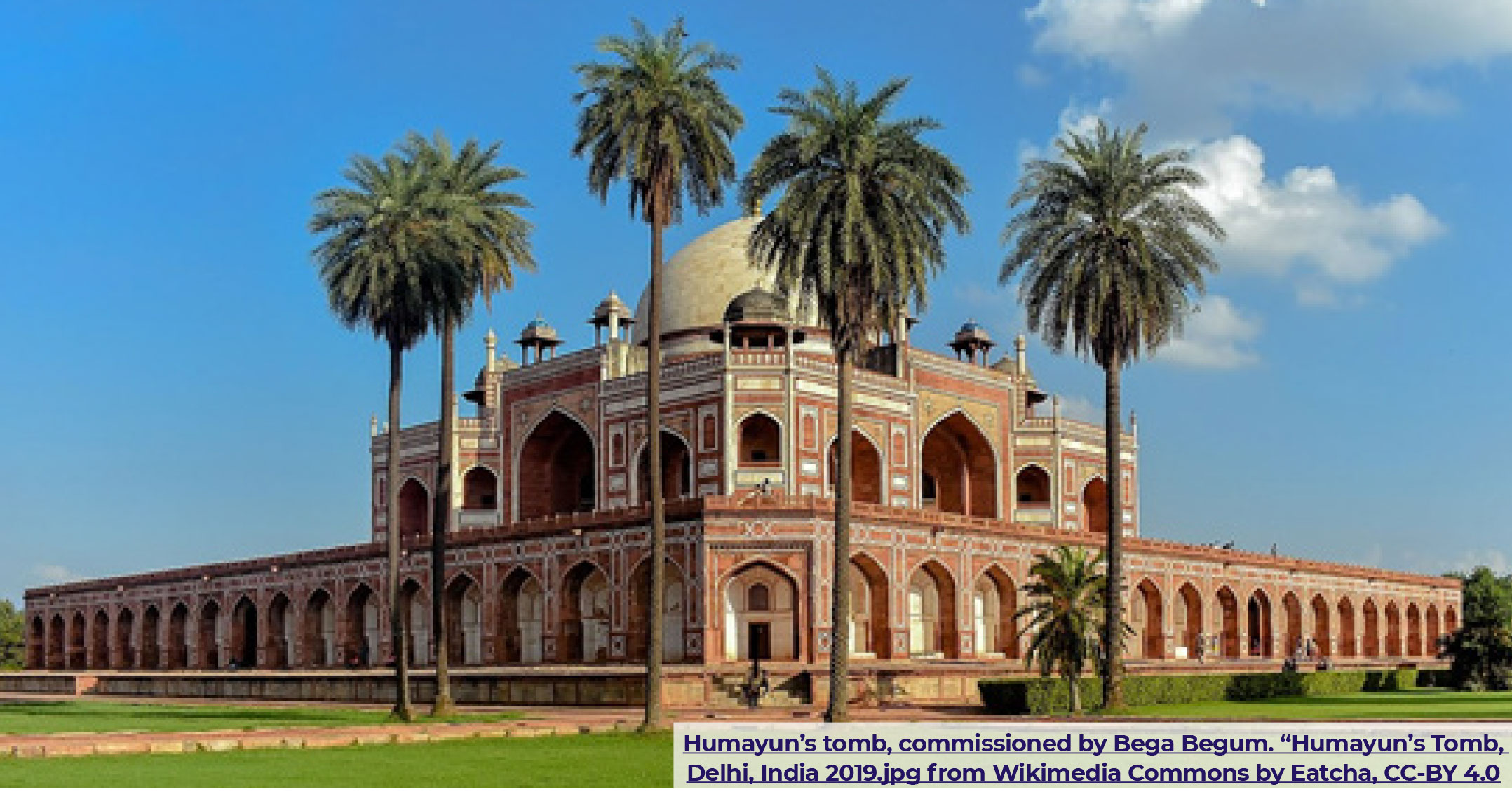

Women have often used their own experiences to theorize and make contributions to Architecture. As a result, at the very core of the work of many female architects, urbanists and historians, has been a sense of collectivism and care. In her essay ‘What would a non-sexist city be like’ Dolores Hayden examines how the phrase, “a woman’s place is the home”[4] has been a driving principle for domestic design in the United States. With houses designed to define and reinforce domestic roles, Hayden, through case studies, reimagines an alternate domesticity. Through restructuring homes and redefining gender roles in domestic spaces, the possibility of sharing domestic labor is considered a reality. Hayden advocates for neighborhoods which are designed to share the work and support the domestic laborers - the women.

Women have often used their own experiences to theorize and make contributions to Architecture. As a result, at the very core of the work of many female architects, urbanists and historians, has been a sense of collectivism and care. In her essay ‘What would a non-sexist city be like’ Dolores Hayden examines how the phrase, “a woman’s place is the home”[4] has been a driving principle for domestic design in the United States. With houses designed to define and reinforce domestic roles, Hayden, through case studies, reimagines an alternate domesticity. Through restructuring homes and redefining gender roles in domestic spaces, the possibility of sharing domestic labor is considered a reality. Hayden advocates for neighborhoods which are designed to share the work and support the domestic laborers - the women.

Yasmin Lari, one of the most prominent architects of Pakistan proposes similar ideas through her work. As the first female architect of Pakistan, Yasmin Lari has made immeasurable contributions to the Architectural field in the country. Her contributions include large corporate projects, but in the last two decades she has focused her energy on the Heritage Foundation which she established in 1980 with her husband. Lari states “It’s not only the right of the elite to have good design” a critical thought and need for a country that has a massive socioeconomic gap. The Heritage Foundation has undertaken relief work and designed low cost homes that are realized through communal building.

Neighborhoods employ local materials designed around the needs of the user but one of the most visible aspects is incorporating space for the women of these communities. Through providing spaces of gathering and sharing labor, resources, learning, and educating, Yasmeen Lari empowers the women of these

devastated communities. Similar to Hayden’s vision and critique of rethinking our domestic spaces, to dismantle boundaries of public and private, isolated and shared, we see it in practice in the many neighborhoods Yasmin Lari has helped remake. Volunteering for the Heritage Foundation in my senior year

as a young designer was pivotal in shaping my vision for what architecture should be. The work done by women through the history of architecture is just a glimpse of what the power of gender equity in design can

do and provides a roadmap to redefine and re-imagine architecture. Perhaps through the balancing of genders, the built world might ever so slowly undo the systemic injustices in place and empower those who

have no agency.

One of the communal structures designed by the Heritage Foundation using bamboo

structure and mud and lime mortar. Image: The Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

References

[1] Schimmel, Annemarie. (2004) The Empire of the Great Mughals. Edited by Burzine K. Waghmar. N.p.: Reaktion Books.

[2] Eraly, Abraham. (2007) The Mughal world: Life in India’s Last Golden Age. N.p.: Penguin Books.

[3] Frank, Karen A. (1989) ‘A Feminist Approach to Architecture’, In Architecture: A Place for Women. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 210-216.

[4] Fainstein, Susan S., and Lisa J. Servon, (2005) Gender and Planning A Reader. United Kingdom: Rutgers University Press.

[5] Wainwright, O. (2020) ‘The barefoot architect: ‘I was a starchitect for 36 years. Now I’m atoning’. The Guardian. Availabe at: https://www.theguardian. com/artanddesign/2020/ apr/01/yasmeen-lari-pakistanarchitect- first-female-jane-drew.

Anam Izhar Ahmed is a Pakistani architectural designer, researcher and educator based in New York City. She holds a Masters in Advanced Architecture design from Columbia University and a M. Arch from Parsons, The New School for Design.