Sometimes being vocal can create a mess.

Jahan, a member of Khwajasira Society (KSS) in Lahore, in speaking about the marginalization of the trans community mentioned how invisibility has protected the community. One might ask; how did this happen? Was the community always on the peripheries? Did it always need protection? If not, what was the status of Khwajasiras in pre-colonial times, in the Indian society? In attempting to answer some of these questions, we will be exploring The Lahore Chronicle newspaper archives (most particularly, their reports on the State of Awadh), along with interview notes from our field visits to KSS. Started in 1849 by Syed Muhammad Azim, The Lahore Chronicle was the one of the first newspapers published in British India. Given that these papers platformed the voices of senior British Residents (officers), we aimed to understand how the social, and moral politics of Indian society was being reconfigured during this time, with a specific focus on the implication this had for the Khwajasira community.

To contextualize, part of the Mughal Empire until 1720s, Awadh became was one of the main Princely States of this region. In 1764, the Company defeated Awadh in the Battle of Buksar and it came under indirect British rule, with the influence of local Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula being reduced. Moreover, the Company also required for them to pay a substantial amount of money for defense. There was a remarkable difference between Awadhi, and nineteenth century British values3, and this marks the start of our exploration.

During this time the Khwajasiras in Awadh assumed an integral role in commanding the military of the state itself.

During this time the Khwajasiras in Awadh assumed an integral role in commanding the military of the state itself. During the reign of Wajid Ali Shah, Padshah or ruler of Awadh, for example, a regular cavalry, consisting of hundred soldiers each, was placed under “the nominal commands of the eunuchs”. Their responsibilities included, according to the newspapers, “contractors for the clothing”, and right to nominate or recommend officers as their deputies. Interestingly, Awadh had a separate force for women, King’s women troopers, called “Beebee Rissaldars” that included female foot soldiers, and mahal guards. These too were commanded by a Khwajasira.

The Nawwabs of Awadh also personally enjoyed a close relation with Khwajasiras. Sought for as guidance, blessings, and entertainment, they were particularly respected by the nobility. Khwajasira Basheer “made a present of a pair of camel leopards to the king”, and also received pigeons from the Khwajasira Dianut. Further, in the late 1840s, the newspaper mentions that a regiment of five hundred cavalry was placed under the Khwajasira Hadjee Shereef. The Company considered Hadjee Shereef’s demand of Rs. 100 from each soldier to be a “corrupt” method of securing a post. After dismissing the Company’s objections, Wajid Ali Shah named Hadjee Shereef joint commander of a new regiment. In this manner, it is important to understand how Khwajasiras were understood as trusted, and loyal companions to the ruler. This suggests that Khwajasiras had a valuable social standing in society, and some were also well off. However, care must be taken to not over emphasize their role, as nawwabs and male literati also undermined high ranking Khwajasiras at courts.

This source consistently downplayed their role, building on half-truths. One newspaper article mentions that while Khwajasiras have played an “important” role, it was an “underhand and secret one”. The officers detested them, as the newspaper mentioned that they exercised “influence…over the King’s mind” so much so that the English Minister “naturally detests them from the bottom of his heart for standing in a measure between him and his sovereign”. Here, it is crucial to note the root of this anxiety. The Resident foresaw “evils that would arise from their active interference in state affairs”, and was, hence, “hostile” to them. Such images of ‘unnatural-ness’ and ‘immorality’ were evoked to mischaracterize them as inherently menacing figures capable of destabilizing the ‘pure’ gender binary if they continue to punctuate society with their presence.

Rebranding of the social standing of Khwajasiras from sacred beings in Hindu mythology, and as significant participants in Indian society to likening them to “filth, disease, contagion, and contamination” was at the heart of this project. By extension, the Awadhi princes and rulers were considered “unmanly” and “sexually immoral”. Good governance was premised on codes of masculinity and this failure in masculinity symbolized failure in governance.

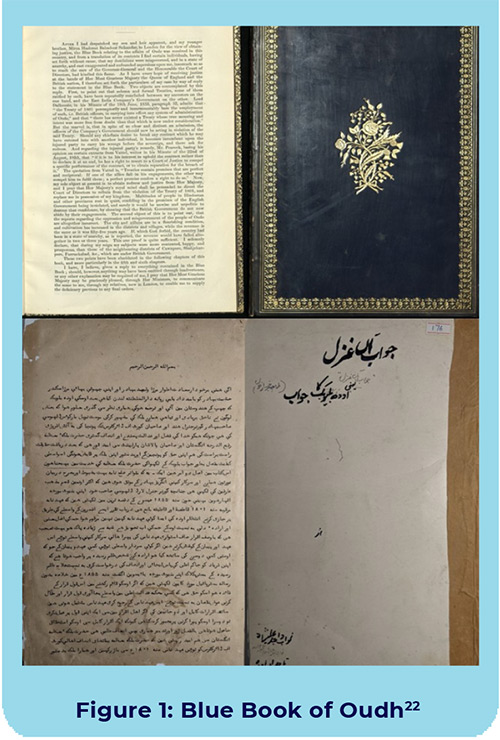

“Eunuchs” were represented as “politically ‘corrupt’”, and this was used as a justification for Awadh’s “maladministration”. Many of these claims are also mentioned in “Oude Blue Book”. King of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah, for example, was deemed as a “weakminded man” because he of his choice to employ “one of his favored eunuchs”, Busheer-ood-Dowlah, as Chuckladar of Roosalabad. Many, including the Resident, interfered and “the nomination of the Eunuchs to the Chuckladarship was put a stop to”. However, Basheer’s servant was the new applicant, and “all that is wanted is the prevention of the responsible and active interference of the eunuchs in the Government”.16 While this echoes Shah’s resistance to conform to the British, the Company pressurized him to submit to Victorian values of gender and politics. The Company began to blame Khwajasiras for the incompetence of the Awadh administration.

On June 20, 1848, the British Resident and Wajid Ali Shah signed a written agreement to prevent Khwajasiras from partaking in governance and official matters, such as any branch of the army, office of Payment, Intelligence, Charge of Corn, Cloth, and other related matters. If they disobeyed, they would be “banished from Oudh (Awadh)”. The only exception was they could still be a part of “His Majesty’s personal Guard”. This transformed the meanings of the role of Khwajasara as their status declined from “slave-nobles” to “Muslim poor of colonial Lucknow”.

(Tidbit: The Blue Book of Oudh, or the “Papers Relating to Oude”, are a collection of parliamentary papers  that documented Wajid Ali Shah as an “incapable” and “inefficient” ruler. Shah did not remain passive; instead, he penned a refutation in English. This refutation has been translated into Urdu, titled “Javab-i an ghazal: tamacah barukhsar-i falan, yaʻni, Bartanvi Avadh Bliu buk ka javab,” meaning “The reply to that ghazal: a slap in the face of someone, or, Reply to the British Awadh Blue Book”, by his great grandson Kaukab Qadr and is kept in The Library of Congress under the Asian Division’s Naqvi Collection).

that documented Wajid Ali Shah as an “incapable” and “inefficient” ruler. Shah did not remain passive; instead, he penned a refutation in English. This refutation has been translated into Urdu, titled “Javab-i an ghazal: tamacah barukhsar-i falan, yaʻni, Bartanvi Avadh Bliu buk ka javab,” meaning “The reply to that ghazal: a slap in the face of someone, or, Reply to the British Awadh Blue Book”, by his great grandson Kaukab Qadr and is kept in The Library of Congress under the Asian Division’s Naqvi Collection).

The framing of events in these sources is also reflective of the logic of maintaining these values intact. In February 1856, Lord Dalhousie annexed Awadh. This newspaper retold events of this annexation, framing ‘facts’ in a colonial discourse. An article published in a July 1856 paper recalls that “Oudh could not long have borne the tyranny of eunuchs, fiddlers, and nautchgirls, abusing the authority of a prince as degraded in spirit as they were in position”. It was, instead, the “high-minded” nobleman like Lord Dalhousie who opposed this structure of rule. This reflects a form of superiority of colonial rationality over north Indian structures of governance that replaced it with “high-caste Hindus”. Major General Outram, quoted former Residents as saying, the king’s “soul, body and estate” are “wholly in the hands of the menials hired to serve his pleasures”. These include Khwajasiras singers and “other improper persons”. As a result, King’s “nature” was portrayed as “frivolous amusements” and “personal gratification”. Here, notions of sexuality, masculinity, domesticity and kinship were at the center of imperial expansion. This refashioning of gender, slavery, and governance is still echoed in the marginalized status of trans community.

Jahan shared that one of the main myths is “Khwajasira ka bacha utha k lay jana” (Khwajasira kidnap children).

Similarly, reflecting on how our system is enmeshed in many “myths”, Jahan shared that one of the main myths is “Khwajasira ka bacha utha k lay jana” (Khwajasira kidnap children). She stated here that this “miscommunication” ought to be repaired. Debates around the Transgender Persons Act 2018, she said, gave rise to the “shaadi myth”. That is, that Khwajasiras and trans people only want to get married and that is why we create all this “drama”, but the reality is something else entirely. These newspaper archives, then, allow us to trace the historical trajectory of the way in which the Khwajasira community, has been imagined, and ‘dealt’ with. Most importantly, it provides us insight into the social, and moral politics governing the regulation of gender and sexuality, and the way in which this violent emphasis on ‘disciplining’ the community, according to Victorian values, paved the way for imperial expansion, as evidenced by the justification given to annex Awadh.

Maheen is a rising senior pursuing a degree in History, with a minor in Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies.

Musfira Khurshid is a rising senior and a student of history at LUMS.