The relationship between a mother and a daughter may be described as one of the most complex dynamics in the modern world. Even when a mother and daughter have a somewhat “good” relationship, it is layered with a myriad of intricacies, meanings, and understandings (or lack thereof). This complexity deeply piqued my interest as it is, but coming across grief memoirs written by women, upon either losing a mother or a daughter, prompted me to delve further into how grief complicates a tricky dynamic. When faced with loss, grief, and death, this desire to tell or hear stories becomes even stronger. Kathleen Fowler, argues that while the “storying” of death and loss has always existed, however, the women’s grief memoir is a relatively recent literary genre. The vitality of this new form comes from its unification of writing and reflection, literary consciousness and societal and personal insight, and the stories of the deceased and the bereaved. The grief memoir fills the gap left by other significant bodies of literature and contributes to a community of the bereaved missing from contemporary grief practices. Grief memoirs written by women were of particular interest to me because I was interested in how these non-fictional stories of loss induce and construct a gendered self.

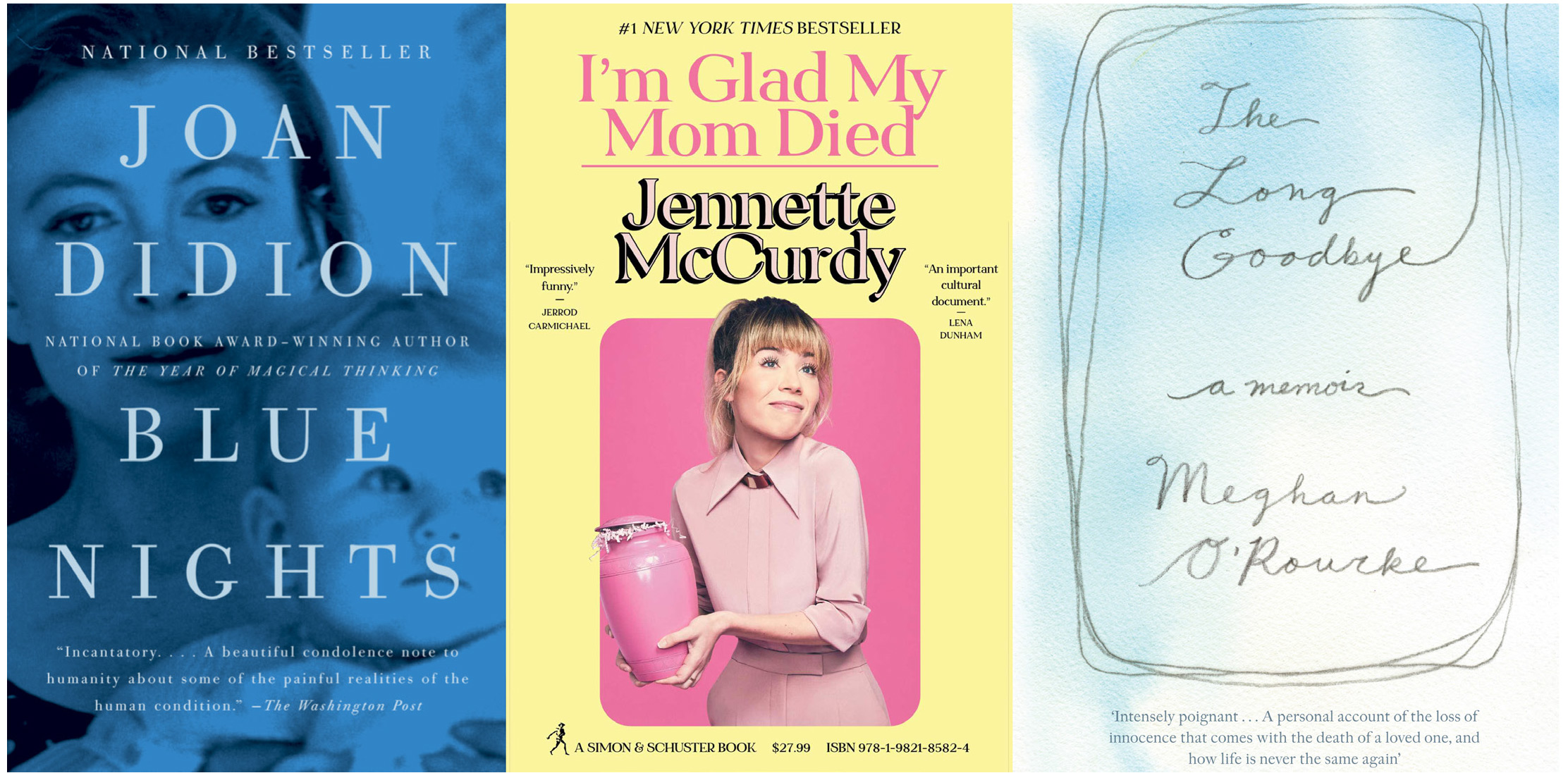

In my research, I explored the genre of the women’s grief memoir using three such memoirs that have defined the last decade: Blue Nights (2011) by Joan Didion, I’m Glad My Mom Died (2022) by Jennette McCurdy, and The Long Goodbye (2011) by Meghan O’Rourke. Each memoir contributes to the greater literary debate about mourning and writing about grief, while maintaining their individual writing styles, structures, and variety of literary features. These memoirs were chosen specifically because each writer avoids a moralistic tone wherein the experience of grief and loss “transformed” them and does not have any clear agenda that gives definitive meanings to loss. Each book allows the reader to interpret the narrative in their own ways and allows them to make their own connections within the broad spectrum of experiences of grief.

I explored how trauma and grief go beyond the boundaries of time and place and how the grief memoirist attempts to deal with this.

As for my theoretical frameworks, Cathy Caruth and Sarah Gilbert provide a substantial foundation for the critical engagement of grief, trauma, and memory, while Helen M. Buss provides incisive analysis that supplemented the three memoirists’ intentional writing through her reflections on the motherdaughter dynamic and how it determines grief.

By examining the motherdaughter dynamic in these memoirs, my research explores the question of identity (who is a daughter? Who is a mother? How enmeshed are these two identities?) and the experience of questioning the role of the mother and daughter in the grief memoir. Through an engagement with “truth”, I explored how trauma and grief go beyond the boundaries of time and place and how the grief memoirist attempts to deal with this specifically in relation to the unique mother-daughter dynamic, and finally, how the resolution of all three memoirs engages with the idea of “recovery” and thus successfully constructs a meaningful confrontation with the fear of loss.

In the first few pages of The Long Goodbye, Meghan O’Rourke shares her definition of a mother: “A mother, after all, is your entry into the world. She is the shell in which you divide and become a life”. This is a notion that I found common throughout all three memoirs, as elucidated by Kathie Carlson, “From her mother a woman receives her first impression of how to be a woman and what being a woman means”. As the narrative progresses, O’Rourke goes into slightly more detail about deriving her sense of identity as a girl and woman from her mother, remembering that rather than looking up to her as a rolemodel, she wanted to be her mother, or live her mother’s life.

The theme of identity, enmeshment and the effect of illness is even stronger in I’m Glad My Mom Died. McCurdy is explicit about the inability to separate herself from her mother, and her mother’s insistence on their unification throughout the memoir, to the point where Gilbert’s notion of the “mortal wrong” in this book is this enmeshment and unification. McCurdy5 begins the narrative through the perspective of her six-year-old self, where it is immediately made clear to the reader that McCurdy’s mother needs to feel needed as a mother in order to derive her sense of self and worth: “She often weeps and holds me really tight and says she just wants me to stay small and young”. This act of emotional manipulation at such a young age affected McCurdy so greatly, that even after her mother’s death, she is unwilling to accept her mother as a flawed person let alone an abusive figure, linked to the concept of “truth” as it exists within the experience of trauma and grief. This internal contradiction is best explained in Helen M. Buss’s terms that daughters identify with their mothers so strongly that to separate themselves calls for a “negative act of denial”, which McCurdy and O’Rourke struggle to engage in, and which Didion only realises through the writing of Blue Nights.

McCurdy’s narrative is also reminiscent of Buss’s observation that the mother is the “primary significant other in many women’s accounts”, and that in the larger culture, the mother is shown as either the saint or victim, or a “monster”. What makes McCurdy’s memoir unique is that she takes us on a journey of her coming to terms with her mother’s abuse after seeing her as a “saint”, but never actually painting her out to be a “monster” either;she shows that a relationship with an abusive mother is multifaceted and sometimes intertwined within normality. While McCurdy acknowledges the unique bond mothers and daughters have in her memoir, she criticizes the glorification of motherhood that others engage in as an extension of explaining the mother-daughter relationship. Gilbert wrote Death’s Door because, at the time, no one had engaged in an in-depth examination of the interplay between the personal, cultural and the literary, paving the way for grief memoirs such as McCurdy’s that aptly examine these intersections.

What makes McCurdy’s memoir unique is that she takes us on a journey of her coming to terms with her mother’s abuse after seeing her as a “saint”, but never actually painting her out to be a “monster” either.

An exploration of this concept from the perspective of a mother, then, is essential to creating a three-dimensional view of the analysis of the relationship between mother and daughter, and of motherhood. Didion is constantly reflecting on these ideas in her memoir, recalling seemingly banal moments from Quintana’s childhood to reassess her role as a mother7; for instance, “The next time a tooth got loose she pulled it herself. I had lost my authority. Was I the problem? Was I always the problem?” Didion engages in a critical reflection8 on her motherhood and the idea of enmeshment between mother and daughter, “Depths and shallows, quicksilver changes. She was already a person. I could never afford to see that”, questioning her role as a dominating figure as opposed to McCurdy’s mother.

In another juxtaposition (or perhaps a parallel) with McCurdy’s experience with her mother, Didion questions, “Had she chosen to write a novel because we wrote novels? Had it been one more obligation pressed on her? Had she felt it as a fear? Had we?”. Didion’s thought process may be juxtaposed with McCurdy’s mother’s here, in that Didion agonizes over whether she pushed Quintana into a profession of her choosing, where McCurdy’s mother felt no regrets over pushing her into acting. However, it also may parallel it in the way that mothers often see their daughters as extensions of themselves without realising.

My final point of analysis was an assertion that these grief memoirs are manifestations of what Caruth identifies as a “complete recovery” from the trauma of losing a mother/ daughter.

In her recollection of Quintana’s childhood and the days leading up to her death in Blue Nights, Joan Didion constantly questions why she did not pick up on signs of Quintana’s mental illness and selfhood, and picks at her possible inadequacies as a mother. “What remained until now unfamiliar, what I recognize in the photographs but failed to see at the time they were taken, are the startling depths and shallows of her expressions, the quicksilver changes of mood. How could I have missed what was so clearly there to be seen?” (Didion 31). This constant self-questioning depicts how Didion as a mother and a grief memoirist attempts to understand and comprehend her grief and the unique dynamic she had with her daughter, without any air of selfvictimisation as a “monster”, as discussed previously.

My final point of analysis was an assertion that these grief memoirs are manifestations of what Caruth identifies as a “complete recovery” from the trauma of losing a mother/ daughter. Caruth claims that a complete recovery from trauma can be determined when its story can be told, and the person can reflect on what has happened and give it a place in their life history, and thus in the whole of their personality, essentially in the form of a memoir. By the end of the memoir, Didion has managed to find a midway point between honouring Quintana’s memory while also fully and completely accepting her death, “The fear is for what is still to be lost. You may see nothing still to be lost. Yet there is no day in her life on which I do not see her.” This, I argue, seems to successfully construct a meaningful confrontation with the fear of loss.

O’Rourke mirrors a similar mindset and experience in her loss, “Am I really she who has woken up again without a mother? Yes I am… Because she is not here, I must mother myself.” Here, we also see an expression of grief and fear simultaneous with an acceptance of the death of the most prominent figure in her life, also landing at a midway point similar to Didion’s upon confronting her biggest fear that “the Person Who Loved Me Most in the World” had died (O’Rourke 69). McCurdy also engages in her own version of this midway point, wherein the processing of her grief, she would sometimes fantasize about what life would have been like if she was still alive and apologized, and supported Jennette in having her own identity, but then realise that she, too, was romanticizing her mother, “Mom made it very clear she had no interest in changing.. I shake my head. I don’t cry. I know I’m not coming back.” Caruth would perhaps describe this as a “complete recovery” from trauma due to McCurdy’s ability to return to her traumatized memories in order to complete them (i.e. acknowledging that her mother abused her), and to give it a place in her life history and autobiography without feeling guilt or shame in her current life.

Grief and trauma can become impossible to live with, and so the memoir becomes an attempt to comprehend it.

Thus, each memoir constructs its own version of Caruth and Gilbert’s conceptualization of the final transitory phase of grief, that is, being able to construct a history of trauma and grief that critically engages with the pain and fear experienced in relation to it.

In the end, I found that the women’s grief memoir is a radical form of writing which coincides with both an increased public discomfort with the mention of death and as well as the recent professional interest in bereavement. Grief and trauma can become impossible to live with, and so the memoir becomes an attempt to comprehend it. Blue Nights, I’m Glad My Mom Died, and The Long Goodbye all combine a narrative of the deceased and the bereaved, personal, and social critical analysis, and writing and reflection to create complex accounts of grief and construct a dialogical mother-daughter discourse. Further research on this topic would include an examination of the roles of class and race in the grief memoir, and how they determine women’s experiences of grief and further complicate the mother/ daughter relationship, a perspective that was beyond the scope of my research at this time.

Rida Arif will graduate with a BA in English and a minor in Sociology/Anthropology from LUMS, where she was a tutor at the Academic Writing Lab (AWL) and Junior Editor of The LUMS Post.